The World of Religions No. 51 – January/February 2012 —

The World of Religions No. 51 – January/February 2012 —

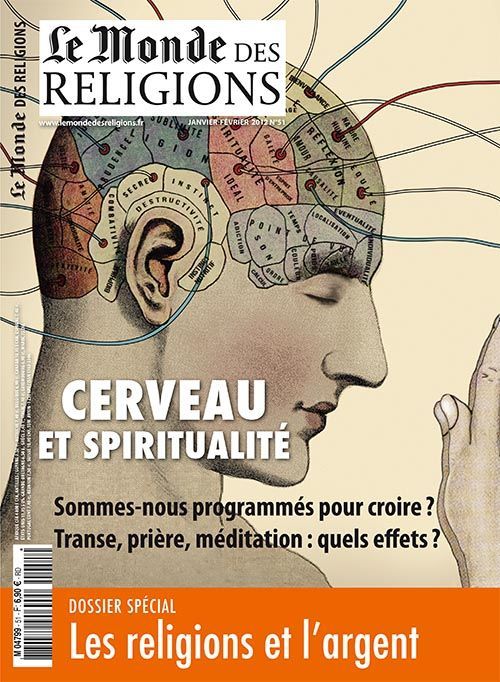

Our dossier highlights an important fact : spiritual experience in its very diverse forms—prayer, shamanic trance, meditation—has a bodily inscription in the brain. Beyond the philosophical debate that results from it and the materialist or spiritualist interpretations that can be made of it, I retain another lesson from this fact. It is that spirituality is first and foremost a lived experience that touches the mind as much as the body. Depending on each person's cultural conditioning, it will refer to very different objects or representations : an encounter with God, with an inexpressible force or absolute, with the mysterious depth of the spirit. But these representations will always have in common the fact that they provoke a shaking of the being, an expansion of consciousness and very often of the heart. The sacred, whatever name or form we give it, transforms the person who experiences it. And it overwhelms them in their entire being : emotional body, psyche, spirit. Yet many believers do not have this experience. For them, religion is above all a marker of personal and collective identity, a moral code, a set of beliefs and rules to be observed. In short, religion is reduced to its social and cultural dimension.

We can point to the moment in history when this social dimension of religion appeared and gradually took over from personal experience : the transition from nomadic life, where man lived in communion with nature, to sedentary life, where he created cities and replaced the spirits of nature – with whom he came into contact through altered states of consciousness – with the gods of the city to whom he offered sacrifices. The very etymology of the word sacrifice – “to make the sacred” – clearly shows that the sacred is no longer experienced : it is done through a ritual gesture (an offering to the gods) intended to guarantee the order of the world and protect the city. And this gesture is delegated by the people, who have become numerous, to a specialized clergy. Religion therefore takes on an essentially social and political dimension : it creates bonds and unites a community around great beliefs, ethical rules and shared rituals.

It was in reaction to this excessively external and collective dimension that, around the middle of the first millennium BC, very diverse sages appeared in all civilizations who intended to rehabilitate the personal experience of the sacred : Lao Tzu in China, the authors of the Upanishads and the Buddha in India, Zoroaster in Persia, the initiators of the mystery cults and Pythagoras in Greece, the prophets of Israel up to Jesus. These spiritual currents were often born within religious traditions, which they tended to transform by contesting them from within. This extraordinary surge of mysticism, which never ceases to amaze historians by its convergence and synchronicity in the different cultures of the world, would shake up religions by introducing a personal dimension that in many ways reconnects with the experience of the wild sacred of primitive societies. And I am struck by how much our era resembles this ancient period : it is this same dimension that increasingly interests our contemporaries, many of whom have distanced themselves from religion, which they consider too cold, social, and external. This is the paradox of an ultramodernity that attempts to reconnect with the most archaic forms of the sacred : a sacred that is experienced more than it is "made." The 21st century is therefore both religious through the resurgence of identity in the face of fears engendered by too rapid globalization, but also spiritual through this need for experience and transformation of being that many individuals feel, whether they are religious or not.