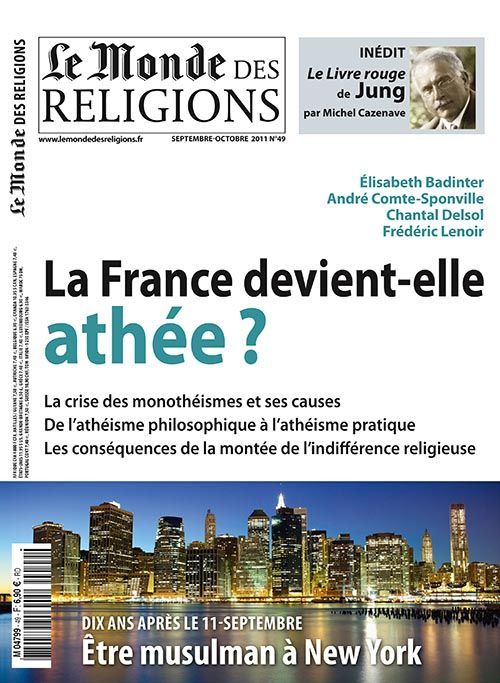

The World of Religions No. 49 – September/October 2011 —

The World of Religions No. 49 – September/October 2011 —

The strengthening of fundamentalism and communalism of all kinds is one of the main effects of 9/11. This tragedy, with its global repercussions, revealed and exacerbated the divide between Islam and the West, just as it was both a symptom and an accelerator of all the fears linked to the ultra-rapid globalization of previous decades and the resulting clash of cultures. But these identity-based tensions, which continue to cause concern and constantly fuel media coverage (the Oslo massacre in July being one of the latest examples), have overshadowed another, entirely opposite, consequence of 9/11: the rejection of monotheistic religions precisely because of the fanaticism they engender. Recent opinion polls in Europe show that monotheistic religions increasingly frighten our contemporaries. The words "violence" and "regression" are now more readily associated with them than "peace" and "progress." One consequence of this resurgence of religious identity and the fanaticism that often accompanies it is a sharp increase in atheism.

While the movement is widespread in the West, the phenomenon is most striking in France. There are twice as many atheists as there were ten years ago, and the majority of French people now identify as either atheist or agnostic. Of course, the causes of this surge in disbelief and religious indifference are deeper, and we analyze them in this report: the development of critical thinking and individualism, urban lifestyles, and the decline of religious transmission, among others. But there is no doubt that contemporary religious violence exacerbates a massive phenomenon of detachment from religion, which is far less spectacular than the murderous madness of fanatics. As the saying goes, the sound of the falling tree drowns out the sound of the growing forest. However, because they rightly worry us and undermine world peace in the short term, we focus far too much on the resurgence of fundamentalisms and communitarianisms, forgetting to see that the real change on the scale of long history is the profound decline, in all strata of the population, of religion and the age-old belief in God.

I will be told that this phenomenon is European and particularly striking in France. Certainly, but it continues to intensify, and the trend is even beginning to spread to the East Coast of the United States. France, after having been the eldest daughter of the Church, could well become the eldest daughter of religious indifference. The Arab Spring also shows that the aspiration for individual freedoms is universal and could well have as its ultimate consequence, in the Muslim world as in the Western world, the emancipation of the individual from religion and the "death of God" prophesied by Nietzsche. The guardians of dogma have understood this well, they who constantly condemn the dangers of individualism and relativism. But can one suppress a human need as fundamental as the freedom to believe, to think, to choose one's values and the meaning one wants to give to one's life?

In the long run, the future of religion, it seems to me, lies not so much in collective identity and the submission of the individual to the group, as was the case for millennia, but in personal spiritual exploration and responsibility. The phase of atheism and rejection of religion into which we are increasingly entering can, of course, lead to rampant consumerism, indifference to others, and new forms of barbarity. But it can also be the prelude to new forms of spirituality, secular or religious, truly founded on the great universal values to which we all aspire: truth, freedom, and love. Then God—or rather, all his traditional representations—will not have died in vain.