Published in L'Express no. 3239 – July 31, 2013 – Interview by Olivier Le Naire –

Published in L'Express no. 3239 – July 31, 2013 – Interview by Olivier Le Naire –

What does the expression "Asian wisdom" encompass?

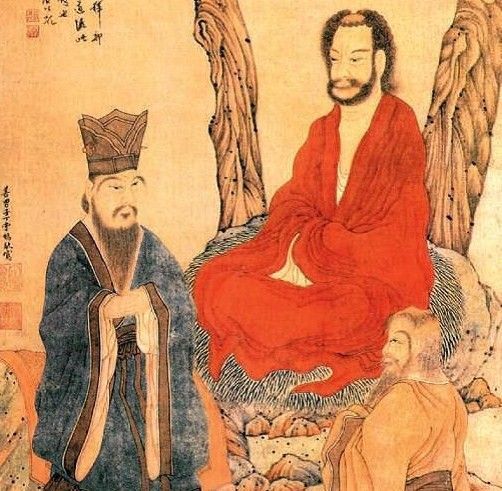

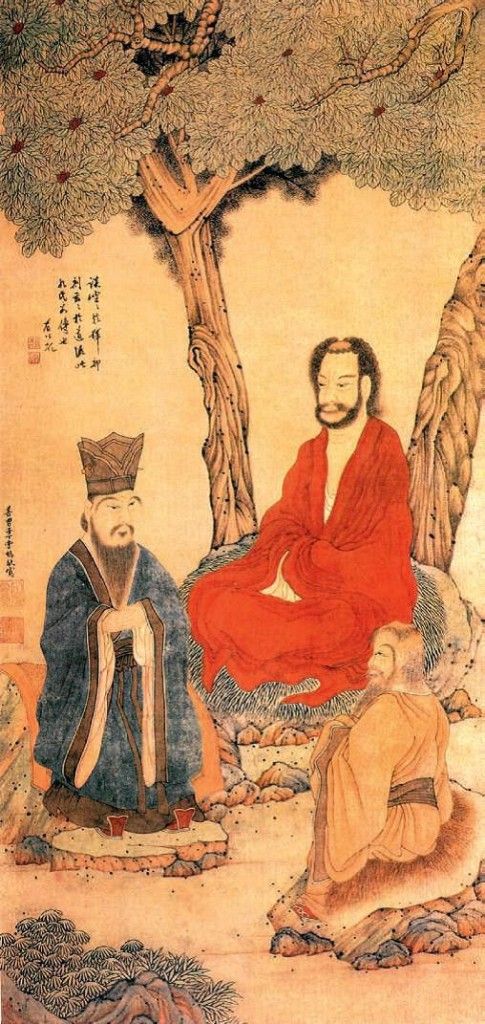

Such different traditions cannot be entirely equated. Some, like Japanese Shintoism, are essentially religious, with beliefs and rituals that play a crucial role in shaping collective identity. At the other extreme, Buddhism is more philosophical and centered on a personal spiritual journey, which aptly justifies the term "wisdom," as it refers to the quest for liberation or a happy life. Hence its universal and easily exportable nature. Hinduism in India, and Confucianism and Taoism in China, fall somewhere in between. True national traditions with diverse rituals, they also offer universal moral principles, worldviews, and spiritual paths that can be shared beyond their origins. It is these dimensions that Westerners seek, rather than their more religious or identity-based aspects.

In any case, we can talk about "religions"... but what is the difference with monotheisms?

If we define religion not by its content (its beliefs) but by its social function, we can apply the term "religion" to all these Asian traditions, just as we do to the major monotheistic traditions. All the world's religions share the common ground of offering collective beliefs, practices, and rituals that create social bonds around an invisible force that takes on very diverse forms or names. The difference lies in the content of what one believes. Monotheistic religions affirm the existence of a creator god who organizes the universe and possesses a personal dimension. We can pray to him; he speaks through the voice of prophets; he cares about us. From this stems a linear dimension of time: from creation to the end of the world willed by God. Asian traditions are closer to nature and offer a cyclical vision of time: there has never been a beginning and there will never be a definitive end to the universe… because there is no creator god external to the world. Whatever name we give it, the Absolute (Brahman, Tao) is impersonal and present in nature as well as in humankind. This does not prevent these traditions from believing in a multitude of manifestations of this ineffable divinity, through gods who are venerated (there are said to be 33 million in India!) or spirits who are feared. Similarly, these wisdom traditions do not contain the notion of a single, revealed Truth, and this is one of the reasons for their success in the West: they tell us that truth is discovered through meditation, knowledge, and spiritual experience.

Does the success of Asian wisdom stem from the fact that it is often based on experience?

Yes, it's concrete; it happens in our bodies and minds. Here, we connect with ancient Greek philosophy. I find it quite extraordinary that all these currents of wisdom, both Eastern and Western, emerged around the same time, around the 6th century BC, within very diverse civilizations previously dominated by major sacrificial religions. We suddenly witness the emergence of a more personal spirituality, of mystical currents that aim to achieve the union of the human and the divine, that question the meaning of life and the possibility of individual salvation or liberation. This period saw the development of Zoroastrianism in Persia and prophecy in Israel, but also the golden age of the Upanishads and the birth of Buddhism in India, the rise of Taoism and Confucianism in China, and the beginnings of philosophy in Greece—a word whose etymology, incidentally, means "love of wisdom." Most philosophers of antiquity defined their discipline as the pursuit of a virtuous, good, happy, and harmonious life—precisely the ambition of Asian wisdom traditions. How can one achieve true and lasting happiness? How can one maintain inner peace regardless of life's events? The questions are the same, even if the answers vary across cultures. The Chinese, deeply connected to nature, speak more of the search for balance and harmony between the complementary polarities of yin and yang, while Buddhists and Greeks emphasize self-knowledge and self-mastery. The Stoics, for example, like those in India, aim for the ideal of the sage who has mastered their passions, is no longer driven by their sensual desires, and manages to order them in order to be happy. And in Epictetus, as in the Buddhist corpus, you will find this idea that there is, on the one hand, what depends on us, which we can transform and improve through self-work, and, on the other hand, external events, over which we have no control, and which require us to accept them, to let go. This is why the philosophical wisdom of Antiquity and Eastern wisdom speak to us modern people: they don't tell us what to believe, but they help us to live.

Don't Westerners idealize a form of Buddhism that they, in reality, know quite poorly?

Yes, like all Asian wisdom traditions, for that matter. Just as Christianity is idealized in Korea or Japan. What comes from elsewhere is always better! Many believe that religious violence is the preserve of monotheistic religions, and indeed, there have been no wars of conquest based on religion in Asia. This hasn't prevented internal violence and bloody rivalries, however. Or a certain form of proselytism, certainly not aggressive, but very effective. We must also remember that Asian societies are still marked by strong misogyny. Many Westerners also idealize Hindu or Buddhist "spiritual masters," who are not always authentic, and who take advantage of this naiveté for enrichment or domination. But, beyond these somewhat external aspects, the main misunderstanding, for me, is something else: while Buddhism advocates self-abandonment, the modern West advocates self-fulfillment.

What does that mean in concrete terms?

We often use Buddhist techniques, particularly meditation, as a tool for personal development: our "self" feeds on these methods to assert itself even more, whereas the goal of Buddhist practice is the dissolution of this "self," considered illusory. As early as 1972, the Tibetan lama Chögyam Trungpa denounced the "spiritual materialism" of Westerners, who "consume" spirituality instead of truly accepting its transformation. But it's not so simple, because beyond the superficial and utilitarian aspect, easily identified and condemned, it is not obvious for a Westerner to become a Buddhist, given that our entire anthropology—from ancient Greece to modernity, including Christianity—is founded on the notion of "person": we are a unique and substantial being who aspires to self-realization. Buddhism, on the contrary, views the individual as a temporary aggregate, and we must, according to it, discover that the self conceived as an autonomous personality is an illusion. This is in order to free ourselves from this illusion and attain nirvana.

So, it's not possible to switch from one religion to another so easily?

We are all deeply conditioned by our history and culture, even if we believe ourselves to be uprooted. Michel Onfray rightly asserts that, even in the most secular West, we remain rooted in a Christian "episteme" (the triple heir of the Jewish, Greek, and Roman worlds), which governs our conception of humanity and the world. Hence this lack of lucidity. The psychologist Carl Gustav Jung stated that one cannot change culture, and therefore cannot change religion, since the two are intimately linked. This echoes what the Dalai Lama says: if you change religion, you will very often find yourself critical of the one you came from and will unconsciously reproduce the patterns of your culture in your new religion. It would therefore be better, according to him, to find spiritual paths within one's own culture that suit us, unless it requires a lifelong commitment—as is the case, for example, with Matthieu Ricard. This seems very true to me, but I also believe that one can, without necessarily becoming Buddhist, Hindu, or Taoist, adopt philosophical viewpoints from the East, such as the concepts of causality, the impermanence of phenomena, the interdependence or balance of all things—viewpoints that are sometimes even validated by contemporary science. One can also, of course, adopt a number of techniques (meditation, yoga, qigong, etc.) to find inner peace. For me, these are invaluable contributions that can help us broaden our understanding of ourselves and the world, and live better lives. Who could complain about that?