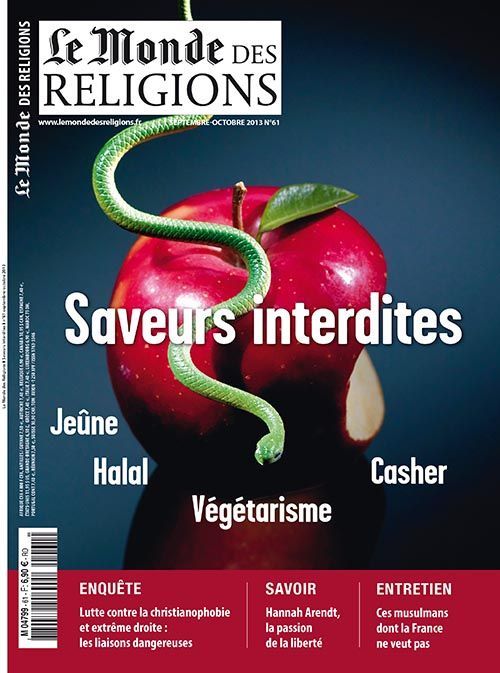

The World of Religions No. 61 – Sept/October 2013 –

The World of Religions No. 61 – Sept/October 2013 –

As Saint Augustine wrote in *On the Happy Life* : “ The desire for happiness is essential to man; it is the motive of all our actions. The most venerable, most understood, most clearly understood, and most constant thing in the world is not only that we want to be happy, but that we want to be nothing but that. This is what our nature compels us to do. ” While every human being aspires to happiness, the question remains whether profound and lasting happiness can exist here on earth. Religions offer very different answers to this question. The two most opposing positions, in my view, are those of Buddhism and Christianity. While the entire doctrine of the Buddha rests on the pursuit of a state of perfect serenity here and now, that of Christ promises the faithful true happiness in the afterlife. This is due to the life of its founder – Jesus died tragically around the age of 36 – but also to his message: the Kingdom of God that he announces is not an earthly kingdom but a heavenly one, and beatitude is yet to come: “ Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted ” (Matthew 5:5).

In an ancient world rather inclined to seek happiness in the here and now, including within Judaism, Jesus clearly shifted the focus of happiness to the afterlife. This hope for a heavenly paradise would permeate the history of Western Christianity and sometimes lead to extremes: radical asceticism and the desire for martyrdom, mortifications and suffering sought in pursuit of the Kingdom of Heaven. But with Voltaire's famous phrase – " Paradise is where I am " – a remarkable reversal of perspective took place in Europe from the 18th century : paradise was no longer to be awaited in the afterlife but achieved on Earth, through reason and human effort. Belief in the afterlife – and therefore in a paradise in heaven – gradually diminished, and the vast majority of our contemporaries began to seek happiness in the here and now. Christian preaching was thus completely transformed. After having insisted so much on the torments of hell and the joys of paradise, Catholic and Protestant preachers hardly ever speak of the afterlife anymore.

The most popular Christian movements—Evangelicals and Charismatics—have fully embraced this new reality and constantly assert that faith in Jesus brings the greatest happiness, even here on earth. And since many of our contemporaries equate happiness with wealth, some even go so far as to promise believers " economic prosperity " on Earth, thanks to faith. This is a far cry from Jesus, who said, " It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God " (Matthew 19:24)! The profound truth of Christianity undoubtedly lies between these two extremes: the rejection of life and morbid asceticism—rightly denounced by Nietzsche—in the name of eternal life or the fear of hell on the one hand; and the sole pursuit of earthly happiness on the other. Ultimately, Jesus did not despise the pleasures of this life, nor did he practice any form of self-mortification: he loved to drink, eat, and share with his friends. He is often seen " leaping for joy ." But he clearly stated that supreme bliss is not to be found in this life. He does not reject earthly happiness, but he prioritizes other values: love, justice, and truth. He thus shows that one can sacrifice one's happiness here below and give one's life out of love, to fight against injustice, or to remain faithful to a truth. The contemporary testimonies of Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Nelson Mandela are powerful examples of this. The question remains: will the gift of their lives find just reward in the afterlife? This is the promise of Christ and the hope of billions of believers throughout the world.

Read articles online from Le Monde des Religions: www.lemondedesreligions.fr