The World of Religions No. 59 – May/June 2013 –

The World of Religions No. 59 – May/June 2013 –

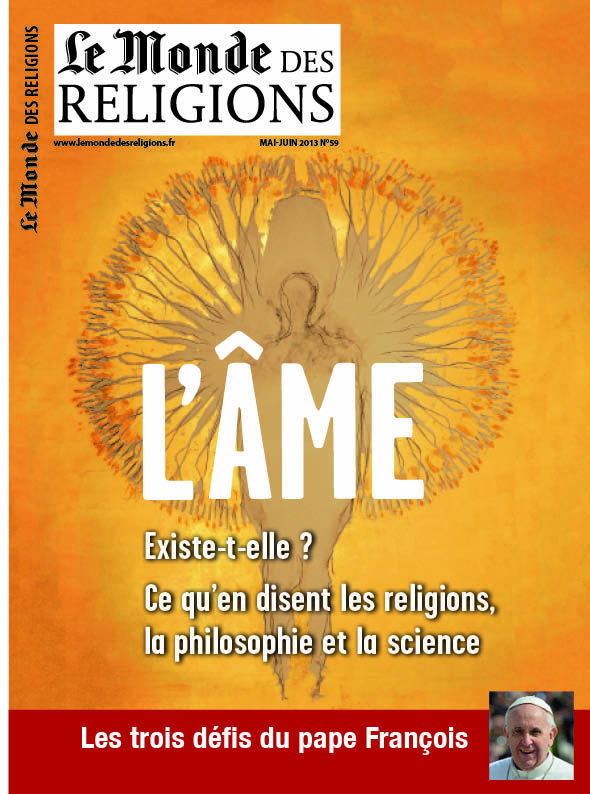

Invited to comment on the event live on France 2, when I discovered that the new pope was Jorge Mario Bergoglio, my immediate reaction was to say that it was a truly spiritual event. The first time I had heard of the Archbishop of Buenos Aires was about ten years earlier, from Abbé Pierre. During a trip to Argentina, he had been struck by the simplicity of this Jesuit who had left the magnificent episcopal palace to live in a modest apartment and who frequently went alone to the slums.

The choice of the name Francis, echoing the Poverello of Assisi, only confirmed that we were about to witness a profound change in the Catholic Church. Not a change in doctrine, nor even likely in morality, but in the very conception of the papacy and the Church's governance. Presenting himself before the thousands of faithful gathered in St. Peter's Square as "the Bishop of Rome" and asking the crowd to pray for him before praying with them, Francis showed in a few minutes, through numerous signs, that he intended to return to a humble understanding of his office. A conception that harks back to that of the first Christians, who had not yet made the Bishop of Rome not only the universal head of all Christendom, but also a veritable monarch at the head of a temporal state.

Since his election, Francis has multiplied his acts of charity. The question now arises as to how far he will go in the immense task of renewing the Church that awaits him. Will he finally reform the Roman Curia and the Vatican Bank, shaken by scandals for over 30 years? Will he implement a collegial mode of governance for the Church? Will he seek to maintain the current status of Vatican City State, a legacy of the former Papal States, which is in blatant contradiction with Jesus' witness of poverty and his rejection of temporal power? How will he also address the challenges of ecumenism and interreligious dialogue, subjects of great interest to him? And what about the challenge of evangelization, in a world where the gap between Church discourse and people's lives, especially in the West, continues to widen? One thing is certain: Francis possesses the qualities of heart and intellect, and even the charisma necessary to bring this great breath of the Gospel to the Catholic world and beyond, as demonstrated by his initial pronouncements in favor of a world peace founded on respect for the diversity of cultures and indeed for all of creation (for perhaps the first time, animals have a pope who cares about them!). The fierce criticism he faced immediately after his election, accusing him of collusion with the former military junta when he was a young superior of the Jesuits, subsided a few days later, particularly after his compatriot and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Adolfo Pérez Esquivel—imprisoned for 14 months and tortured by the military junta—stated that the new pope, unlike other clergymen, had “no connection whatsoever with the dictatorship.” Francis is thus enjoying a period of grace that may inspire him to take any bold step. Provided, however, that he does not suffer the same fate as John Paul I, who had raised so many hopes before dying enigmatically less than a month after his election. Francis is undoubtedly right to ask the faithful to pray for him.