Le Monde des religions no. 42, July-August 2010 —

Le Monde des religions no. 42, July-August 2010 —

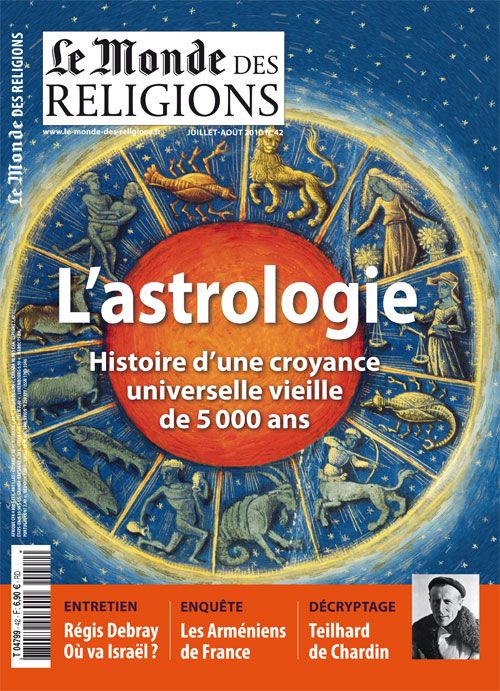

It's astonishing, especially for a skeptic, to see the enduring nature of astrological beliefs and practices across all cultures of the world. From the earliest civilizations, China and Mesopotamia, there isn't a major cultural area that hasn't witnessed the flourishing of astrological belief. And while it was thought to be moribund in the West since the 17th century and the rise of scientific astronomy, it seems to have risen from the ashes in recent decades in two forms: popular (newspaper horoscopes) and cultivated – the psycho-astrology of the birth chart, which Edgar Morin doesn't hesitate to define as a kind of "new science of the subject." In ancient civilizations, astronomy and astrology were intertwined: rigorous observation of the celestial vault (astronomy) allowed for the prediction of events occurring on Earth (astrology). This correlation between celestial events (eclipses, planetary conjunctions, comets) and terrestrial events (famine, war, the death of a king) is at the very foundation of astrology. Even though it is based on millennia of observations, astrology is not a science in the modern sense of the term, since its foundation is unprovable and its practice subject to countless interpretations. It is therefore a symbolic knowledge, based on the belief that there is a mysterious correlation between the macrocosm (the cosmos) and the microcosm (society, the individual). In ancient times, its success stemmed from the need for empires to discern and predict by relying on a higher order, the cosmos. Interpreting the signs of the sky allowed them to understand the warnings sent by the gods. From a political and religious perspective, astrology has evolved over the centuries toward a more individualized and secular interpretation. In Rome, at the beginning of our era, people consulted an astrologer to determine the suitability of a particular medical procedure or career project. The modern revival of astrology reveals more of a need for self-knowledge through a symbolic tool, the birth chart, believed to reveal an individual's character and the broad outlines of their destiny. The original religious belief is discarded, but not the belief in fate, since the individual is supposed to be born at a precise moment when the celestial vault manifests its potential. This law of universal correspondence, which thus connects the cosmos to humankind, is also the very foundation of what is called esotericism, a kind of multifaceted religious current parallel to the major religions, which in the West draws its roots from Stoicism (the world soul), Neoplatonism, and ancient Hermeticism. The modern need to connect with the cosmos contributes to this desire for a "re-enchantment of the world," typical of postmodernity. When astronomy and astrology separated in the 17th century, most thinkers were convinced that astrological belief would disappear forever, reduced to mere old wives' tales. A dissenting voice emerged: that of Johannes Kepler, one of the founding fathers of modern astronomy, who continued to draw up astrological charts, explaining that one should not seek a rational explanation for astrology, but simply acknowledge its practical efficacy. Today, it is clear that astrology is not only experiencing a resurgence in the West, but continues to be practiced in most Asian societies, thus fulfilling a need as old as humanity itself: finding meaning and order in such an unpredictable and seemingly chaotic world.

I extend my sincere thanks to our friends Emmanuel Leroy Ladurie and Michel Cazenave for everything they have contributed through their columns in our newspaper over the years. They are passing the torch to Rémi Brague and Alexandre Jollien, whom we welcome with great pleasure.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yo3UMgqFmDs&feature=player_embedded