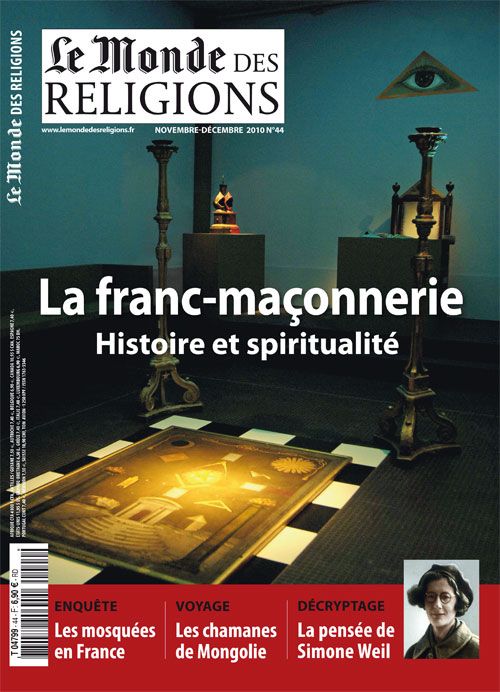

Le Monde des religions no. 44, November-December 2010 —

Le Monde des religions no. 44, November-December 2010 —

The tremendous success of Xavier Beauvois's film Of Gods and Men fills me with profound joy. This enthusiasm is certainly surprising, and I would like to explain here why this film moved me and why I believe it has moved so many viewers. Its first strength lies in its restraint and deliberate pace. No grand speeches, little music, long takes where the camera lingers on faces and gestures, rather than a series of rapid, alternating shots like in a film trailer.

In a hectic, noisy world where everything moves too fast , this film allows us to immerse ourselves for two hours in a different temporality, one that leads to introspection. Some may not find it engaging and may feel a little bored, but most viewers experience a profoundly enriching inner journey. The monks of Tibhirine, portrayed by admirable actors, draw us into their faith and their doubts. And this is the film's second great strength: far from any Manichean approach, it shows us the monks' hesitations, their strengths, and their weaknesses.

Filming with striking realism, and with the invaluable support of the monk Henri Quinson, Xavier Beauvois paints a portrait of men who are the antithesis of Hollywood superheroes: tormented yet serene, anxious yet confident, constantly questioning the wisdom of remaining in a place where they risk being murdered at any moment. These monks, whose lives are so different from our own, become relatable. Believers and non-believers alike are moved by their unwavering faith and their fears; we understand their doubts, we feel their deep connection to this place and to the local people.

This loyalty to the villagers among whom they live, and which will ultimately be the main reason for their refusal to leave, and thus for their tragic end, undoubtedly constitutes the third strength of this film. For these Catholic religious figures have chosen to live in a Muslim country they deeply love, and they maintain a relationship of trust and friendship with the local population, demonstrating that the clash of civilizations is by no means inevitable. When people know each other, when they live together, fears and prejudices disappear, and each can live their faith while respecting that of others.

This is what the prior of the monastery, Father Christian de Chergé, movingly expresses in his spiritual testament, read in voice-over by Lambert Wilson at the end of the film, when the monks are kidnapped and depart for their tragic fate: “If one day—and it could be today—I were to fall victim to the terrorism that now seems to target all foreigners living in Algeria, I would like my community, my Church, my family to remember that my life was given to God and to this country […]. I have lived long enough to know myself complicit in the evil that, alas, seems to prevail in the world, and even in that which might strike me blindly […]. I would like, when the time comes, to have that moment of lucidity that would allow me to ask for God’s forgiveness and that of my fellow human beings, while also wholeheartedly forgiving whoever might have harmed me […].”

The story of these monks, as much as a testimony of faith, is a true lesson in humanity.